Market Outlook: The Market Fears A Credit Crisis

Good Morning HDI!

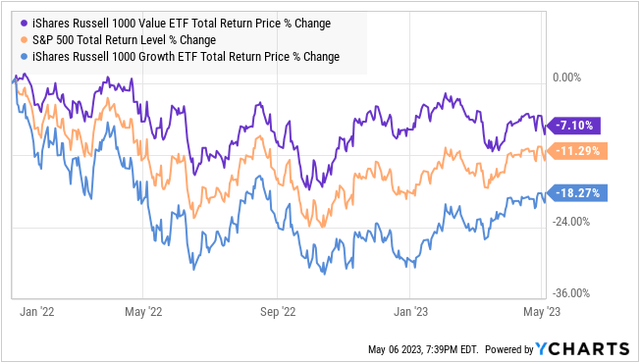

Since the bear market started in 2022, "Value" stocks have outperformed "Growth" stocks. Several times, the iShares Russell 1000 Value ETF (IWD) flirted with returning to 2022 highs. At the same time, the Russell 1000 Growth ETF (IWF) has spent most of the time 15%+ below highs.

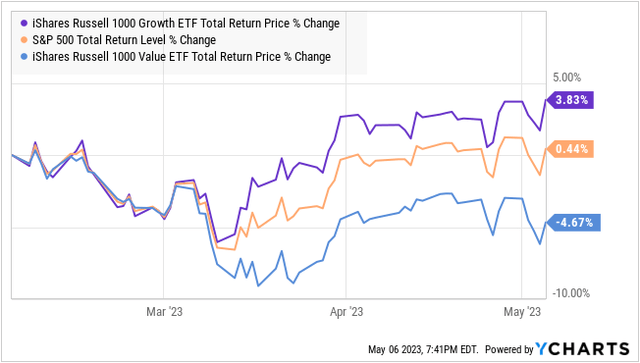

We have seen a shift in the past couple of months as bank failures started in March. Since March, "Growth" stocks have been outperforming.

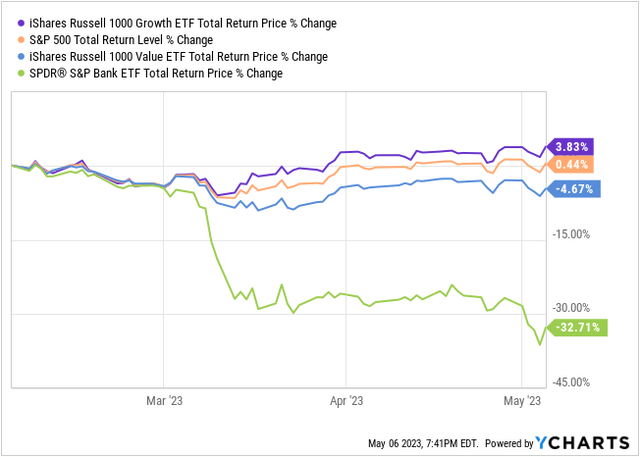

This is directly due to renewed concerns over credit risk and the financial system. After all, banks usually fall into the "Value" stock category. The S&P Bank ETF (KBE) is down nearly 33% in the past 3 months.

Many other "Value" stocks have been impacted as they are related to lending – either as lenders themselves or companies that borrow money. Value stocks tend to be overwhelmingly in mature businesses that produce current cash flow and frequently use debt to fuel their earnings. Growth stocks tend to be in less established businesses and typically carry lower debt levels.

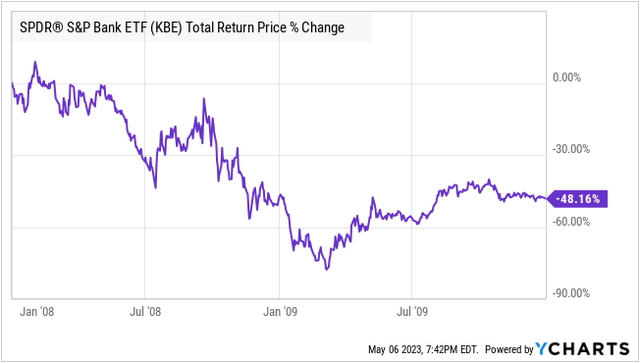

This collapse of bank stock prices reminds many of the Great Financial Crisis ('GFC'). The collapse over the past couple of months is very similar in size to the collapse seen in June and July of 2008. Which, in hindsight, was just the beginning of a much deeper fall.

Given the two charts, it is natural for investors to make a comparison. Is 2023 going to be a rerun of the GFC? Today, we will take a look at the similarities and the differences.

Are There Really A Lot Of "Bad" Loans?

If you were a casual watcher of television news, you would be convinced that banks were failing because they had a bunch of super-risky loans that were defaulting left and right. This simply is not happening right now.

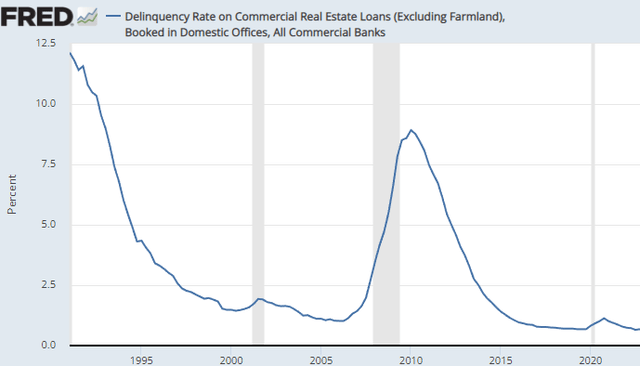

Here is the commercial real estate loan default rate at banks: Source

St. Louis Fed

In Q2 2008, it was 4.15%. The default rate likely increased last quarter, but it was 0.68% in Q4 2022. It is safe to say that the default rate is nowhere near the ballpark of 4%. Based on the banks that have reported so far, the Commercial Real Estate ('CRE') default rate for loans in banks was likely still well under 1% in Q1.

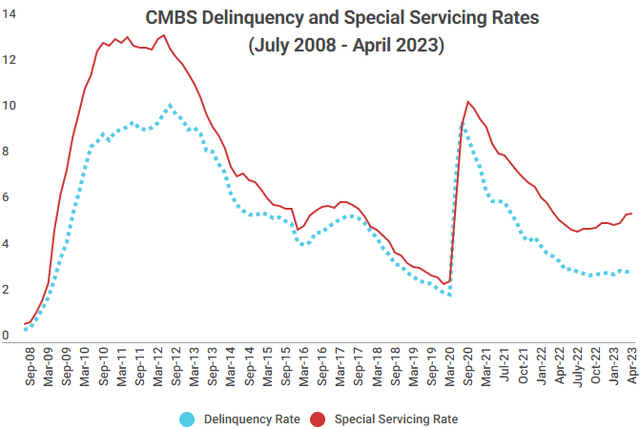

What about all the defaults you have been reading about in the news? Without exception, these have been Commercial Mortgage-Backed Security ('CMBS') loans. The CMBS delinquency rate is 3.09%, well below historical averages but much higher than the CRE loans at banks. Source

Trepp

The special servicing rate has increased, and that indicates that the borrower is working with a "special servicer," and there is some sign of potential distress. A rise in that rate is often a precursor to a rise in delinquencies.

When watching the news, it is important to recognize the distinction between CMBS loans, which are non-recourse loans that large PE firms like Brookfield or Blackstone are perfectly willing to walk away from the second the economics stop making sense, and the usually much smaller CRE loans that are held on bank balance sheets. As a refresher, our market outlook from April 9th covered this difference more in-depth.

None of the banks that failed, failed because of "risky" loans to anyone. None of them had particularly large levels of defaults. Their zero-risk loans got them in trouble—specifically, their holdings of U.S. Treasuries and Agency MBS. Deposits are available on demand, while the Treasuries and agency MBS they held don't mature for 10+ years. That becomes an issue when an unusually large number of customers are trying to take out their deposits all at once, and the price of U.S. Treasuries and Agency MBS is much lower than when the securities were bought. It doesn't matter that the par value is guaranteed in 10 years if the bank needs the cash today.

Treasury and MBS prices are down for one reason: The Fed. The Fed hikes rates by decreasing the price of short-term Treasuries, and the Longer-term treasuries and MBS tend to follow.

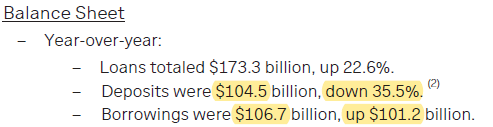

In Q1, First Republic (OTCPK:FRCB) had only 0.08% of their loans that were non-performing, accounting for 0.06% of their total assets. That isn't going to sink a bank. What killed them was the exodus of essentially all of their depositors. Here are the highlights that mattered and ultimately caused the bank to be seized: Source

FRCB Q1 2023 Earnings Release

The $104.5 billion in deposits included the $30 billion in deposits that major banks made in March to try to bail out FRCB. The 35.5% decline is year-over-year. In December, FRCB had $176.4 billion in deposits. So in total, FRCB saw $101.9 billion, 60% of its December deposits, withdrawn. That was offset partially by other banks depositing $30 billion, but it was like trying to patch up a burst water pipe with scotch tape. FRCB borrowed $101.2 billion to meet its obligations to depositors. But borrowing $101.2 billion isn't free.

The bottom line is that no bank can survive a fractional banking system, with 60% of its depositors demanding their money back within three months. The three banks that failed all had similar issues.

This differs from the mortgage crisis, where banks saw their balance sheets threatened by mortgage defaults and realized losses on CMOs. Banks that are able to retain depositors won't have problems. This is why systemically, the Fed is likely seeing this as a lower risk as the very large banks have seen deposits rise. During the GFC, all banks were impacted by credit losses; today, it is certain banks that are experiencing depositors fleeing. Generally, mid-sized regional banks experience reductions in deposits, but even within this group, experiences can vary widely, with some seeing extremely large reductions, many seeing modest reductions, and some seeing no reductions at all.

It is possible that banks start seeing their commercial real estate portfolios experience rising defaults, but we need to keep in perspective that this is currently speculation of the future, not what is happening right now.

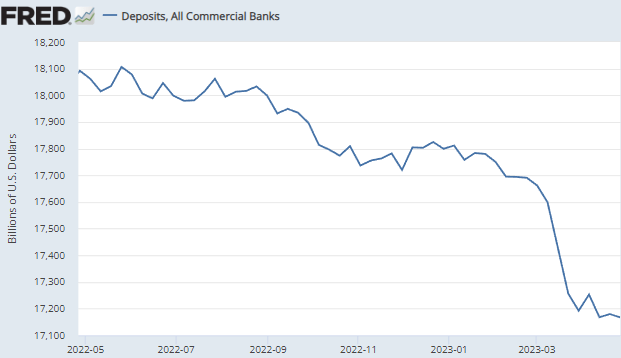

Deposits Are Still Declining

In the big picture, deposits are still declining at banks. Source

St. Louis Fed

You can see the massive dropoff in March. April was more of the steady decline seen last year, which is generally manageable. This decline is inevitable as the Fed hikes interest rates and depositors realize they can get a higher short-term yield from T-bills. Banks can only combat this by increasing the interest they offer to depositors, which directly reduces profits. So it is a fine line for banks to walk, paying enough interest to make the decline in deposits manageable while at the same time maintaining their profit margins.

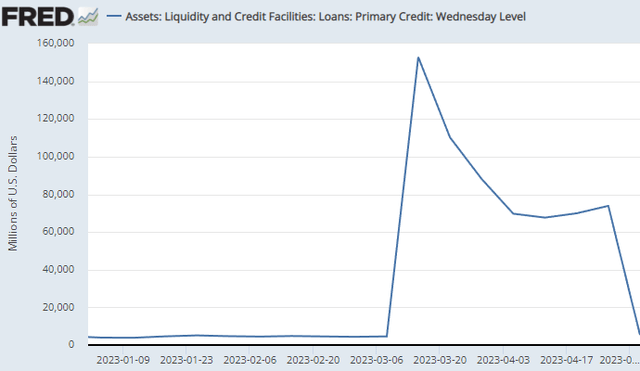

"Discount Window" Loans

One measure of stress at banks is the "discount window" loans that the Federal Reserve makes to banks. Banks use this as a temporary source of liquidity. It is expensive and requires the banks to post collateral, so we can think of it as a last-resort option for banks. With the end of First Republic, the outstanding balance of this credit line declined over 90% to only $5 billion. Source

St. Louis Fed

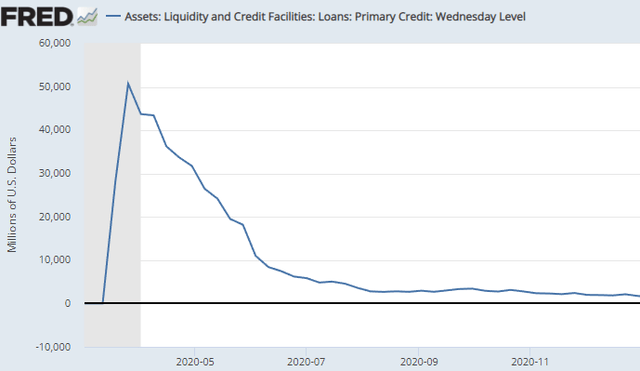

Before March, the balance ranged from $4-$5 billion, so this indicator would suggest that the stress on banks is over. This is very different from what we have seen historically. During COVID, it declined slowly over several months. Source

St. Louis Fed

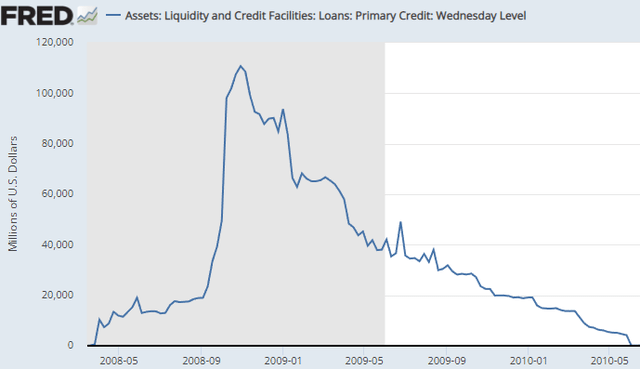

During the GFC, it built up slowly before skyrocketing and was elevated for two years. Source

St. Louis Fed

The names of the banks that use this facility aren't released until two years after they borrow. However, it likely is not a coincidence that FRCB was shut down the same week that the borrowing plummeted over 90%. FRCB was almost certainly one of the largest borrowers utilizing the discount window. This indicates that there might not be another shoe that might drop.

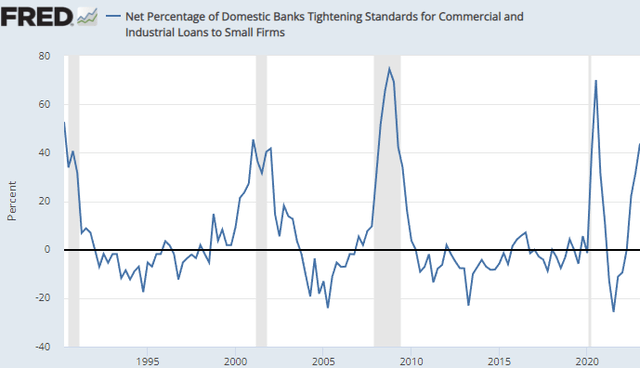

Credit Standards

The worst-case scenario is that banks with declining deposits and a higher capital cost will tighten their lending standards. Naturally, a bank that is concerned about its own balance sheet will want to limit lending and lend only to the highest quality borrowers. Surveys of senior loan officers suggest that tightening standards are happening right now.

Historically, a rapid tightening of lending standards has been a good predictor that a recession will happen soon, COVID being an exception. Source

St. Louis Fed

Though it is worth noting that tightening lending standards necessarily leads to a financial crisis, standards tightened in the early 1990s and the early 2000s, but quality companies were still able to access credit. During the GFC, even high-quality credits had difficulty borrowing at reasonable prices. But looking at whether standards are tightening is not sufficient to tell us if a credit crisis will happen. A better indicator of that risk is credit spreads.

Credit Spreads

When discussing yields, a "spread" is the difference between one yield and another. This can get confusing because it is easy for a speaker to say "the spread" in a conversation and assume the listener knows which spread is being talked about.

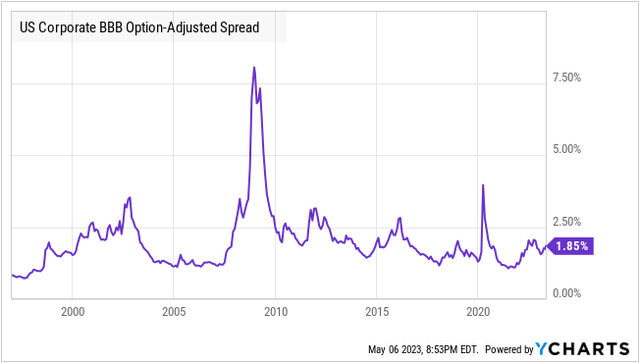

One topic that has been hot over the past months is "credit spreads," which is the difference between the yield banks are charging for loans and U.S. Treasuries of similar duration. When the duration is adjusted for any options that the borrower has to prepay the debt, it is known as the "option adjusted spread." Watching this spread illustrates how much premium lenders are demanding to take on risk. When the spread is lower, it implies that it is easier and cheaper for borrowers to take on more debt. When it is higher, it suggests that there is a lack of willing lenders and borrowers are paying a high premium. Here is the Corporate BBB Option-Adjusted Spread (OAS).

BBB is "investment grade" loans. If this spread skyrockets as it did during the GFC, that would be horrible for the economy. It means that even Investment Grade companies can't rely on being able to borrow money, and in the case of the GFC, even if they could borrow money at a 7.5% spread, the cost increase had a material impact on their financial outlook, often leading to a credit downgrade and even-higher borrowing costs.

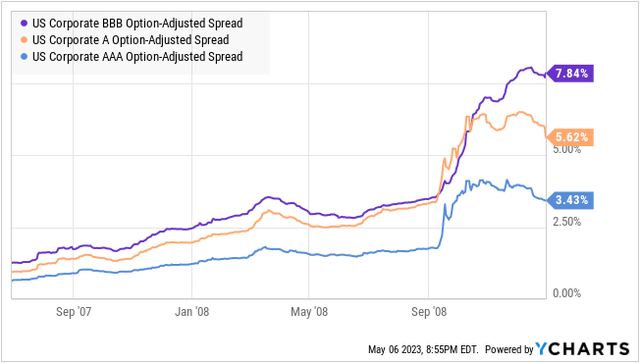

If we zoom in on the GFC, the OAS for various Investment-Grade and better credits looked like this:

This is what some commentators are fearing. Note that in 2008, the BBB OAS was over 2.5% in January and gradually got higher throughout the year. Even A-rated spreads were over 2.5% by April, and then the economy fell off the rails six months later, and even AAA credit spreads went over 3%. In other words, even the highest quality credits were having trouble borrowing. That is what a "credit freeze" looks like because even with sterling credit, borrowers were heavily incentivized not to borrow. It wasn't that banks feared AAA-credit borrowers would default; it was that banks didn't have the capital they were willing to lend.

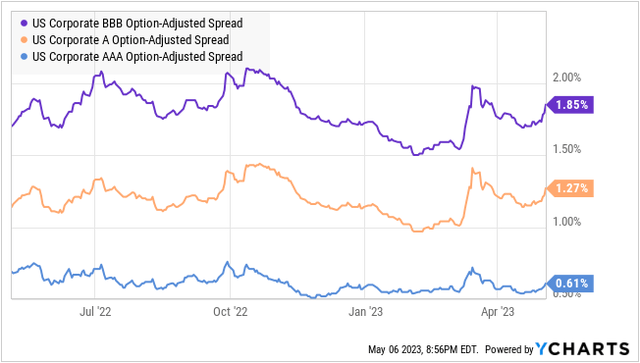

Here is a look at these same spreads over the past year:

Note that they did spike up in March with the banking turmoil and remained above their 52-week lows in February. However, they are also below their 52-week highs in October and are not terribly high in the big picture. We are not seeing the steady upward trend we saw in 2007-2008.

So while there are tightening credit standards, banks are generally still willing to lend. We will keep watching these trends for signs of another credit crisis. For now, I continue to believe that we will have a recession, but we will not see a 2008-style credit crisis, and I do not see the banking issues over the past two months as making one likely.

The Cause Of Defaults And Bankruptcies

The reason this matters is that defaults and bankruptcies happen most frequently at maturity. Especially in the world of corporate debt, where most loans are "interest-only." The borrower will make interest payments and then, at maturity, will owe the principal.

Most borrowers don't have cash on hand to repay the debt. Their plan is to refinance it and pay off the old loan with a new loan. Ironically, it is usually only companies that are facing financial strain that are going out of their way to repay loans with cash and deleverage. Companies that believe they are doing well and have strong earnings will typically assume they are going to be able to borrow and refinance, so they don't set funds aside to repay debt.

If banks are unwilling to lend because they are in trouble and not due to any credit risk for the borrower, then a borrower with no real financial trouble could suddenly be facing insolvency because they can't repay a loan at maturity.

Few borrowers ever struggle to make interest payments, even C-rated borrowers. It is the maturity of debt that causes a default. Therefore, when lenders tighten up standards, you typically see default rates spike up as borderline borrowers are denied. If banks stop lending to higher credit borrowers like B to BBB-rated borrowers, then default rates could skyrocket, and there could be a credit crisis.

What Does This Mean For Our Investments?

For many investments in the HDI portfolio, whether there is a credit crisis or not could have a very significant impact. The HDI Model Portfolio is exposed to credit risk in three ways: We own lenders, we own funds that hold debt, and we own borrowers. Let's take a look at how changes in credit spreads and the risk of a credit freeze could impact them.

- Lenders

Business Development Companies ('BDCs') and commercial mREITs (like ARI, ACRE, and BRSP) are known as "alternative" or non-banking lenders. These are companies that directly lend money to borrowers but are not structured as banks.

On the surface, widening credit spreads are positive for them. After all, the wider that credit spreads are, the higher yields lenders receive. This is most visible in BDCs which borrow at fixed interest rates and lend at floating rates. As interest rates went up, we've seen numerous dividend hikes, supplements, and special dividends from BDCs in our portfolio.

Our commercial mREITs have also seen earnings going up significantly. Every single one of our commercial mREITs saw significant earnings per share growth year-over-year.

These alternative lenders have advantages over banks. The largest is that they are not dependent upon depositors who can pull their capital at any second. They have permanent equity, so this gives them the ability to hold loans until maturity, where a bank might be forced to sell loans at bad prices in order to free up cash to honor a withdrawal.

Yet, every advantage comes with a disadvantage. The risk for BDCs and mREITs is that they are also borrowers. They use bonds, secured credit lines, or securitize their loans to leverage up and improve returns. This could potentially become an issue if they violate a covenant, are unable to refinance their own debt, or in the case of BDCs, the law limits their leverage to 2.0x equity.

Both BDCs and commercial mREITs compete with banks for loans. So if banks are reducing their lending and tightening their standards, BDCs, and mREITs will be in higher demand. The management of Triple Point Venture Growth (TPVG) was very bullish on their earnings call about the void left by Silicon Valley Bank, which was very active in their niche of Venture Capital backed companies. Without the option of turning to a bank, a larger number of these companies will be turning to BDCs like TPVG to meet their needs. These alternative lenders will have less competition and, therefore, will have a wider selection of potential borrowers to choose from.

Of course, the catch is that these alternative lenders must have capital available to lend. Many of their current borrowers have the plan of refinancing through a bank at maturity, and if banks are unwilling to lend, it will fall back on the BDC or mREIT to refinance the loan, increase the size of the loan or let it default. In Q1, we did see an increase in credit concerns among our commercial mREITs, as borrowers were unable to refinance.

Defaults alone typically are not a big deal in the big picture. In both cases, these lenders have significant collateral and the ability to mitigate a large portion of their credit losses even after a default. However, it is crucial that the lender has enough flexibility in their balance sheet to ensure that they have time and capital to obtain the best possible recovery. The BDCs and commercial mREITs in the HDI Model portfolio have strong balance sheets using moderate to low levels of leverage. If you are expanding beyond the HDI Model Portfolio in these sectors, make sure they have similarly strong balance sheets.

The strength or weakness of the balance sheet will separate the companies in these sectors that will be able to profit the most if default rates remain benign and credit keeps flowing. It will also determine which companies might be at risk of permanent capital losses if a credit freeze happens.

- Credit Funds

The HDI Model Portfolio has exposure to various types of credit funds. CLO funds, bond funds, and preferred funds are all part of our portfolio. Higher credit spreads for these funds mean lower prices and higher yields.

CLO funds are a particularly interesting risk/reward because CLOs have a "reinvestment" period. As borrowers repay their loans at par, the CLO reinvests the received principal. With loan prices in the $80-$90 range, a CLO is receiving $100 for every repayment and buying an extra $10-$20 in principal. With low default rates, this grows the amount of interest being received considerably. Loan prices have been below $100 for over a year now, and actual defaults have been low, creating a money-printing environment for CLOs. This is why XFLT hiked its already nosebleed high dividend.

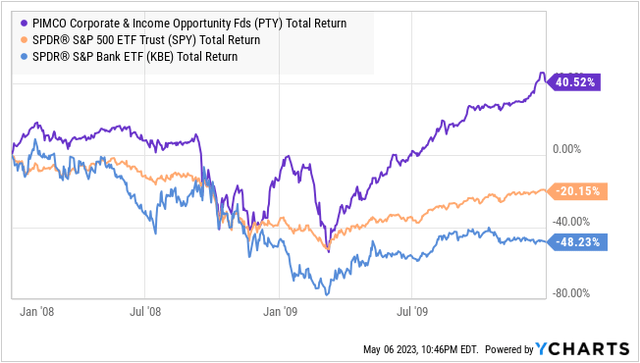

Other credit funds, like the PIMCO CEFs, are in an environment that is full of opportunity, with many bonds trading below par value. This introduces the opportunity for extreme outperformance.

Consider PTY back during the GFC. It crashed with everything else "financial," but while banks were crashing and dumping mortgages at pennies on the dollar, PIMCO was buying them up hand over fist. The recovery was strong, and PTY was able to manage the crisis without cutting the dividend.

Anytime there is distress in the credit markets, it creates risk. When a borrower defaults and goes bankrupt, the losses are usually significant and permanent. However, even when default rates are very high – most borrowers don't file for bankruptcy and they repay their loans in full.

When prices crash, the sellers are the losers. The funds that are capable of buying are the winners. PIMCO demonstrated this during the GFC, and I am confident it would do so again if we see a similar environment.

- Borrowers

Most publicly traded companies fall into the category of borrowers. This is especially true among companies that have established mature businesses. To provide competitive returns, companies use debt. In the HDI Model Portfolio, we have exposure to equity REITs, utilities, MLPs, and telecoms that are all borrowers.

How do credit spreads impact borrowers? In general, the higher the credit spreads, the more expensive it is to borrow. The tighter credit spreads are, the better for borrowers because it means they are paying less in interest expense for the same amount of capital. In the absence of all other variables, lower interest rates and tighter credit spreads are beneficial to any company that borrows money.

In general, credit spreads being a bit high aren't really a big deal to most companies. The cost of borrowing goes up, but healthy companies won't have a problem dealing with that challenge. If we see a full-on credit freeze and spreads skyrocketing as they did during the GFC, then it could become a problem for any company that borrows.

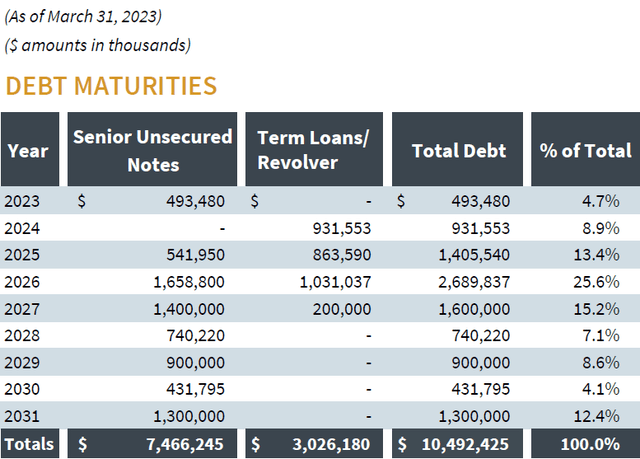

As investors, we can protect ourselves by being aware of what debt a company has maturing and ensuring that they have good plans for dealing with it. For example, Medical Properties Trust (MPW) has been criticized for its debt load. Yet, when we look at the maturity schedule, we can see that relatively little debt is maturing in 2023 and 2024: Source

MPW Q1 2023 Supplement

MPW has over $300 million in cash on hand, $770 million in availability on their revolving line of credit, as well as several sales transactions that are under contract, which are expected to provide $1.4 billion in cash proceeds this year. MPW's plan is to pay off their 2023 and 2024 debt in full and deleverage, yet if one or more of the planned transactions doesn't occur, MPW still has enough cash and availability on their revolver to pay off the debt maturing this year. This is what we mean when we say a balance sheet is "flexible" – MPW has multiple options for repaying the bonds maturing in 2023, so whether they can take out more debt this year or not is irrelevant. If there is a credit freeze, it doesn't impact MPW's ability to pay off its near-term maturities.

When evaluating any individual company, you want to look at the balance sheet, and in particular, the maturities occurring in the next two years, and ask yourself what management's plan is to deal with that debt and whether the company has the liquidity to manage if that plan doesn't work out.

We do this for all of the holdings in the HDI Model Portfolio and are comfortable that the companies we hold will be able to manage their debt load even if it becomes more difficult to refinance. Any company with significant debt maturities in 2023 or 2024 that you can't identify how they would repay those maturities if they were unable to refinance is a higher risk.

Conclusion

The failure of First Republic, combined with the Fed being determined to hike again with a relatively hawkish speech from Powell, shook the markets. Fear, uncertainty, and doubt were stirred up for many investors. Many investors remember the Great Financial Crisis, and the market responded like another similar crisis was upon us.

However, looking at the data, this time is definitely different. Banks are not having credit problems. There is no evidence that the loans banks hold are high risk. In fact, the data so far suggests that the loans held by banks are performing far better than the loans we see that aren't held by banks in the CMBS market.

The bank failures were all caused solely by fleeing depositors, and while many banks are seeing declining deposits, there were a few that saw particularly large withdrawals. Bank borrowings from the Fed's Discount Window have declined back to normal levels, suggesting that as of last Wednesday, no other banks were desperate enough to use that facility. That lever could be used in the future, but in the past, we've seen a much more gradual decline because the facility was being used by many banks instead of just a handful. Simply put, there is a lot of reason to believe that bank failures aren't likely to become as widespread as we saw during and following the GFC.

Credit spreads are elevated relative to 2021 but remain quite low in the big picture. We are seeing nothing like the steady climb up we saw in 2007-2008. Banks are tightening their lending standards, but that is very different from saying that banks have tight lending standards. Like a water spigot, turning it down isn't the same as turning it off.

As investors, we don't want to be blind to the risks. But, at the same time, we don't want to become overreactive when some talking head on TV pontificates about the end of the world. We can protect ourselves by paying attention to the details of the companies we invest in.

The best way to protect ourselves is to watch the balance sheets. Lenders with strong balance sheets will benefit in the long run when they can get loans at great terms when weaker lenders cannot compete. Borrowers with flexible balance sheets will have the luxury of not being forced to refinance at poor terms. They will be able to wait for the crisis to pass and then refinance at favorable terms.

When the market prices start swinging, it is more important than ever that you have confidence in the fundamentals of the companies you invest in. This will allow you to invest in companies that will survive and thrive, taking advantage of dips in the market to grow your income!