The Hidden Costs of Reshoring

The Hidden Costs of Reshoring: Research Article

For the past three decades (and in some ways stretching back up to five decades), the U.S. has been in a relative industrial decline.

More specifically, the share of the U.S. economy that has been involved with manufacturing and related physical industry has declined, and the share of total global manufacturing held by the U.S. has declined as well.

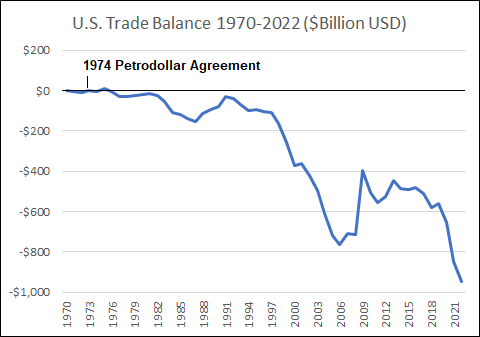

We can see this manifested in our structural trade deficit:

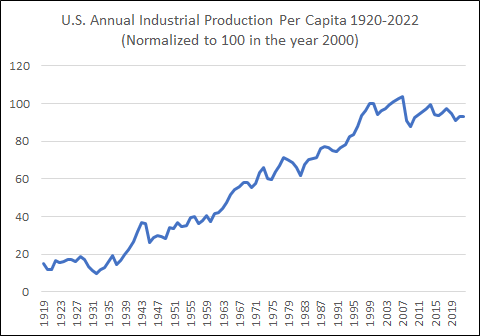

And we can see it in our industrial production per capita:

To some extent this is to be expected; as a country grows in wealth it tends to shift a bit more towards services, and begins to rely on developing countries to supply it with physical goods. However, a number of countries like Switzerland, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and (at least until their recent energy problems) Germany have been successful at maintaining large industrial bases within rather wealthy countries.

The challenge with de-industrialization is that an economy can become hollowed-out, and/or it can face national security issues during a cold war type of environment or during various logistical emergencies. In other words, it’s just not just about access to plastic trinkets; it’s about access to critical things we don’t think about like medical dyes, military components, or even just basic tools that we use for everything else.

So, the themes of “onshoring” or “reshoring” or “nearshoring” have become a hot topic lately, to some extent on the corporate level but especially on the federal level. It refers to the idea of moving manufacturing facilities back to the U.S. or to nearby countries, so that supply chains in general are shorter, less complex, and more resilient. And along these lines, various stimulus efforts have gone into encouraging a boom in domestic manufacturing.

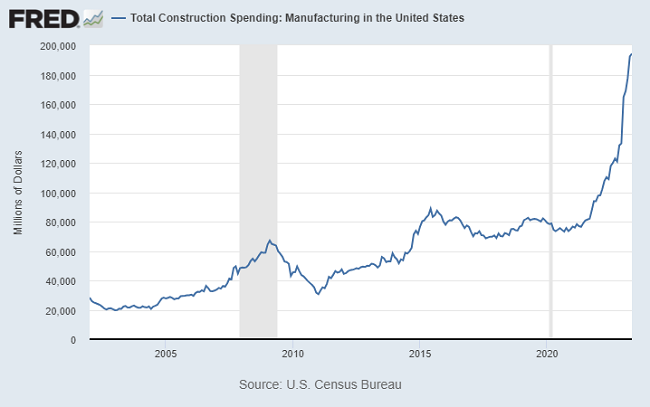

And it is showing up in the data. This chart shows annualized spending on the construction of manufacturing facilities:

The U.S. used to run sub-$100 billion per year in manufacturing construction expenditure, and now it has more than doubled. That’s tangible, even after adjusting for inflation.

However, to provide context to the situation, the U.S. is currently heavily reliant on China’s industrial base that is worth many trillions of dollars. So, this extra $100+ billion just puts us in the first inning here, if this is indeed to be the start of a reversal.

Running the Numbers

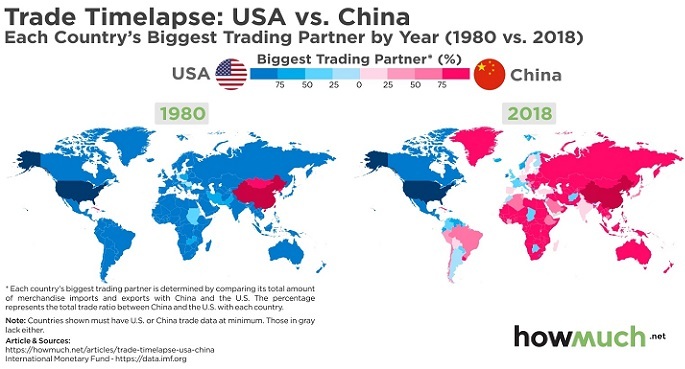

For decades, the United States was a larger trading partner than China for most countries. However, by the late 2010s, China had flipped the U.S. in this regard, and it has only tilted further in China’s favor since then:

Chart Source: How Much

The ability to be the world’s largest trading partner requires both making stuff and having the logistics to organize and ship that stuff. Along those lines, among the top 10 container ports in the world, seven are in China, one is in Korea, one is in Singapore, and one is in the Netherlands. To find the U.S. on the list we have to dig down into the top 20 and top 30 container ports.

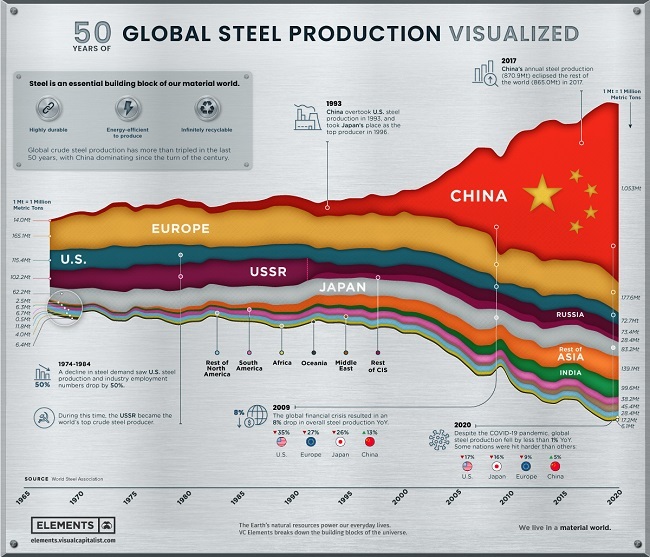

China now produces more steel than the rest of the world combined (and more than 12x as much as the U.S.):

Chart Source: Visual Capitalist

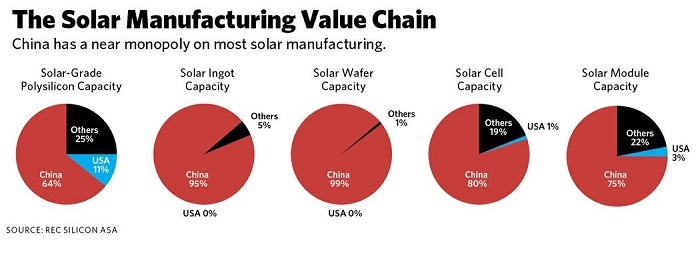

China is by far the world leader in solar panels. In terms of market share, they are more important for the global solar market than Saudi Arabia is for the global oil market.

Chart Source: The American Prospect, REC Silicon

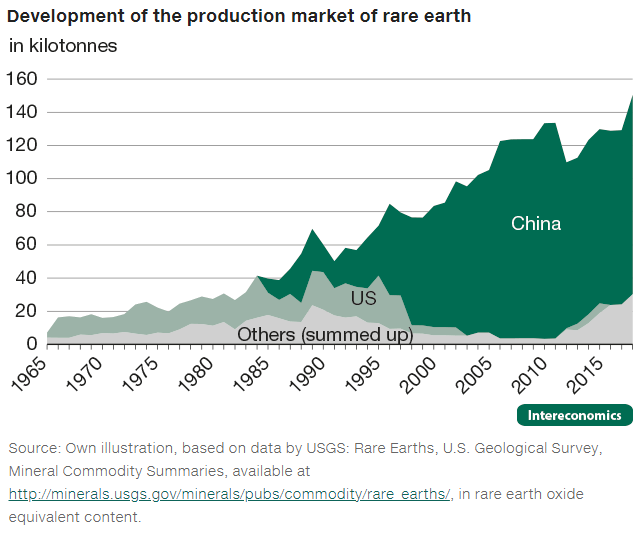

For rare earth elements broadly, which are widely used throughout the electronics industry including the alternative energy industry, China produces more than the rest of the world combined. In recent years, the rest of the world (ex-U.S.) has been regaining a minority share. Rare earth elements are not particularly rare, but they are found in low concentrations and thus tend to be environmentally destructive to extract and refine. Most wealthy regions don’t want to deal with that.

Chart Source: Intereconomics

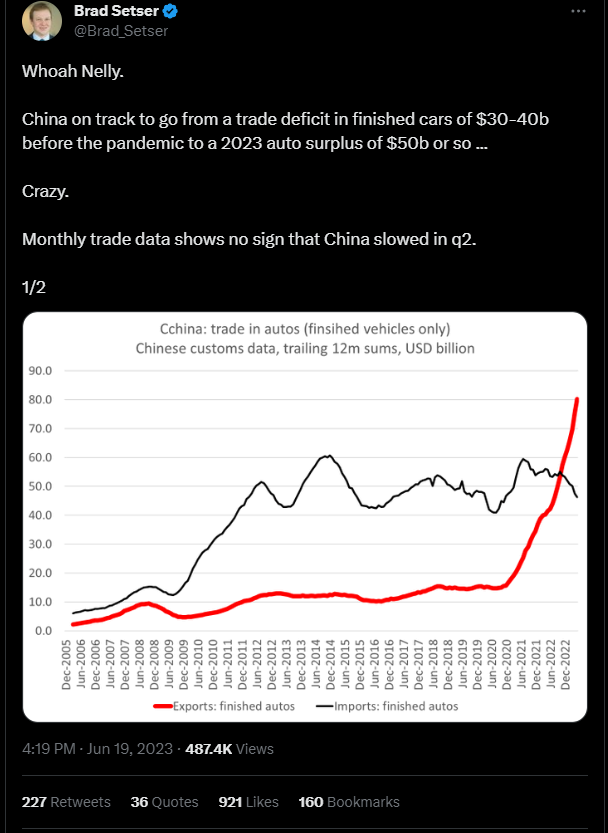

Just within the past three years, China’s auto exports have hockey-sticked in terms of growth. Last year China surpassed Germany and this year they are rivaling Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter. We don’t see them in the United States but if you travel around the world, you’ll see a lot more Chinese cars on the road than just a few years ago.

Here in 2023, China also officially put their first commercial airplane (the Comac C919) into service. The world now has the ABC’s of commercial aviation: Airbus of Europe, Boeing of the U.S., and Comac of China, which was an intentional naming choice on their part to show their ambitions to compete on that level. Currently the main two are Airbus and Boeing, with Embraer of Brazil at a distant third (with less than a tenth of the revenue of either Airbus or Boeing).

The introduction of Comac has been a 15-year development process that began in 2008 and is now live in 2023, and I suspect that over the next 5-10 years their commercial aviation capacity will ramp up like their auto production capacity has.

Energy and Labor: The Hard Part

When people describe the reshoring effort to bring some of that industrial capacity back to the United States, they usually just focus on the first order details: the manufacturing facilities themselves. “It won’t be old heavy industry”, they say. “It’ll be automated, additive manufacturing. This can all run much cheaper now.”

And some of that is indeed true. 21st century manufacturing will trend in a more automated and additive direction than 20th century heavy industry did. But that doesn’t mean reshoring manufacturing is trivial. The actual building of a manufacturing facility is the easy part; it’s everything else in and around it that is hard.

A recent WSJ article “Why America’s Largest Tool Company Couldn’t Make a Wrench in America” highlighted an example:

A highly automated Texas factory was supposed to bring the manufacturing of Craftsman mechanics’ tools back to American shores. The $90 million project was doomed by equipment problems and slow production.

This comes right after TSM, the world’s largest semiconductor company that has been trying to bring production to the United States, reported delays until 2025 due to insufficient skilled labor. As Ars Technica reported:

A TSMC spokesperson told Ars that it typically takes between 2.5 and three years to “build an advanced process fab of similar scale.” Construction on the Arizona fab began in 2021 with what TSMC Chairman Mark Liu described as “an aggressive schedule,” and TSMC “already finished building the shell of the building” but is now “in a phase of handling and installing the most advanced and dedicated equipment,” the spokesperson said. Completing that phase has been delayed, because Liu said, “there is an insufficient amount of skilled workers with the specialized expertise required for equipment installation in a semiconductor grade facility.”

That brings us to the second and third order details. Industrial capital (e.g. manufacturing facilities) is just one part of the equation. We also need sufficient energy capital to power it all, and sufficient human capital to install, operate, and maintain it all.

To quantify some of the energy capital, or more specifically the electricity subset of that, China currently produces nearly twice as much electricity as the United States. Here are the annual numbers via Enerdata:

- China: 8.8 TWh

- USA: 4.5 TWh

- India: 1.8 TWh

- Russia: 1.2 TWh

- Japan: 1.1 TWh

In China’s case as an example, the fact that they currently dominate the solar manufacturing supply chain isn’t just because they have the right manufacturing buildings, although that’s a part of it. Producing polysilicon is energy-intensive. Refining it into wafers is energy-intensive again. China uses coal power for the majority of this. But it’s not just the coal- it’s also the groundwater used in all of the cooling for power generation facilities, and it’s the extensive electrical transmission and distribution infrastructure (which is very intensive in terms of steel, aluminum, and copper inputs).

In other words, China has a lot of power capital, and they have been willing to pay the environmental costs of wielding that much power capital.

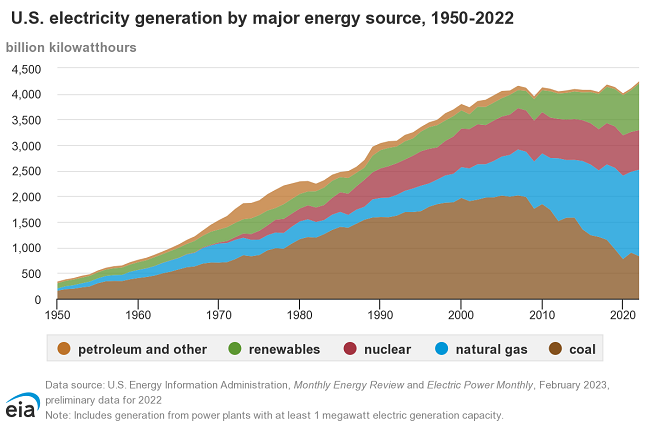

In contrast, U.S. electricity production has been approximately flat for the past two decades (which is when our industrial production flat-lined as well, as we shifted these things increasingly over to China):

Chart Source: EIA

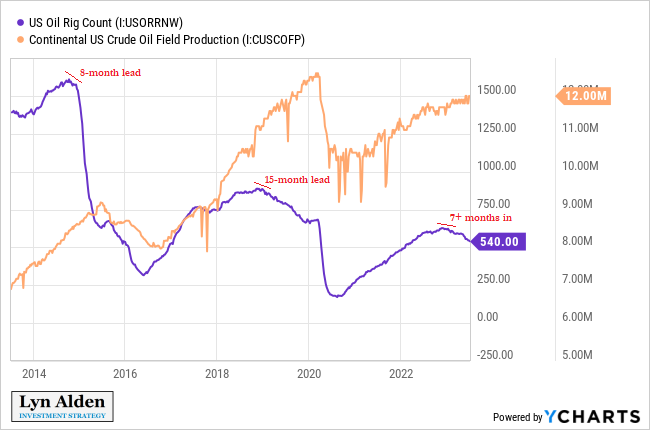

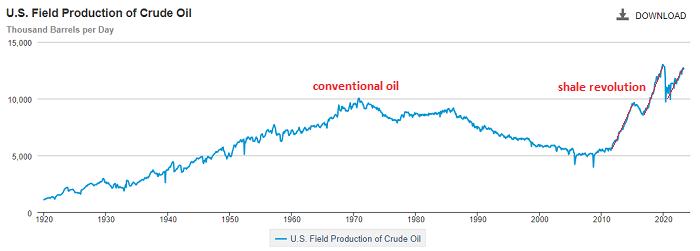

The bright light in the U.S. energy landscape has been the strong uptick in shale oil production. The combination of new technology, a low cost of capital during the 2010s decade, and the willingness to operate at a loss with external financing, led to a rapid increase in U.S. oil production after a long decline of conventional production:

However, shale oil production has fast decline rates, and the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. The cost of capital is higher now, energy investors expect a profit, and many pools of capital have divested from the industry. Going forward, it’ll require more expenditure in order to maintain current or higher levels of shale production, and a lot of that expenditure will need to come from the industry’s own profits.

However, shale oil production has fast decline rates, and the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. The cost of capital is higher now, energy investors expect a profit, and many pools of capital have divested from the industry. Going forward, it’ll require more expenditure in order to maintain current or higher levels of shale production, and a lot of that expenditure will need to come from the industry’s own profits.

Chart Source: YCharts

In terms of human capital, the the past two generations in the United States have been incentivized to work in finance, software, and healthcare. As we have let our industrial capacity stagnate, it has to led to a stagnation in accumulated human capital for this area. It takes years to acquire sufficient technician skills to run these types of facilities. And much innovation comes from hands-on iteration; people working on the facility floor identify problems and propose changes to iterate the process and improve it over time.

So, when we imagine the idea of U.S. reshoring, we must also consider the pathways of energy reshoring (which is expensive and comes with various environmental impacts) and skilled technician labor reshoring (which takes time to re-accumulate).

In other words, rebuilding our industrial capacity is like turning a giant ship- it’ll be a very big process. It’ll require multifaceted capital accumulation, and various bottlenecks such as labor shortages or electrical requirements are likely to keep popping up in the form of unexpected delays and cost overruns as we try to re-accumulate that diverse type of capital.

Final Thoughts: Investing Implications

The prior decade and a half was mainly about intellectual/technical capital accumulation, including software, electronics, cloud infrastructure, and so forth. At the foundation of this era, the introduction of the consumer smartphone with a third party app store and extensive mobile bandwidth is what led to a massive runway of innovation and growth. That combination was a powerful set of building blocks for all sorts of developers to innovate quickly with, and will continue to be.

This focus came at the cost of physical/industrial capital stagnation, at least outside of Asia. Our physical infrastructure aged, our power capacity stagnated, and the supply/demand balances for many types of commodities have tightened. These things do tend to go in cycles.

I continue to view the next decade as a more physical/industrial investment period. Even as tech like AI transforms the way we work and play, it won’t change our need for significant physical investment in infrastructure and energy systems.

As the world becomes increasingly multipolar, we should expect the positioning and fighting over natural resources to intensify. Achieving and maintaining ownership to key infrastructure, minerals, and energy production will likely become increasingly important.